Header Bidding 101: from waterfall to parallel bidding

The evolution of programmatic advertising, from waterfall to parallel bidding

Header Bidding, also known as pre-bidding, started to gain momentum in 2015, by promising publishers to sell every ad impression at its real market value, determining the evolution of programmatic advertising from waterfall to parallel bidding. Until then, programmatic advertising had relied on the waterfall approach, where publishers’ true earning diminished due to the prevalence of the second-price model auction. This model satisfied the interests of advertisers in paying less for every ad impression, decreasing earnings for publishers.

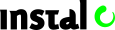

By May 2018, according to e-marketer, news and content, communities, utilities, and e-commerce were the main verticals that adopted header-bidding RTB technology and more than 75% of publishers adopted a client-side wrapper, a server-side wrapper or a hybrid wrapper.

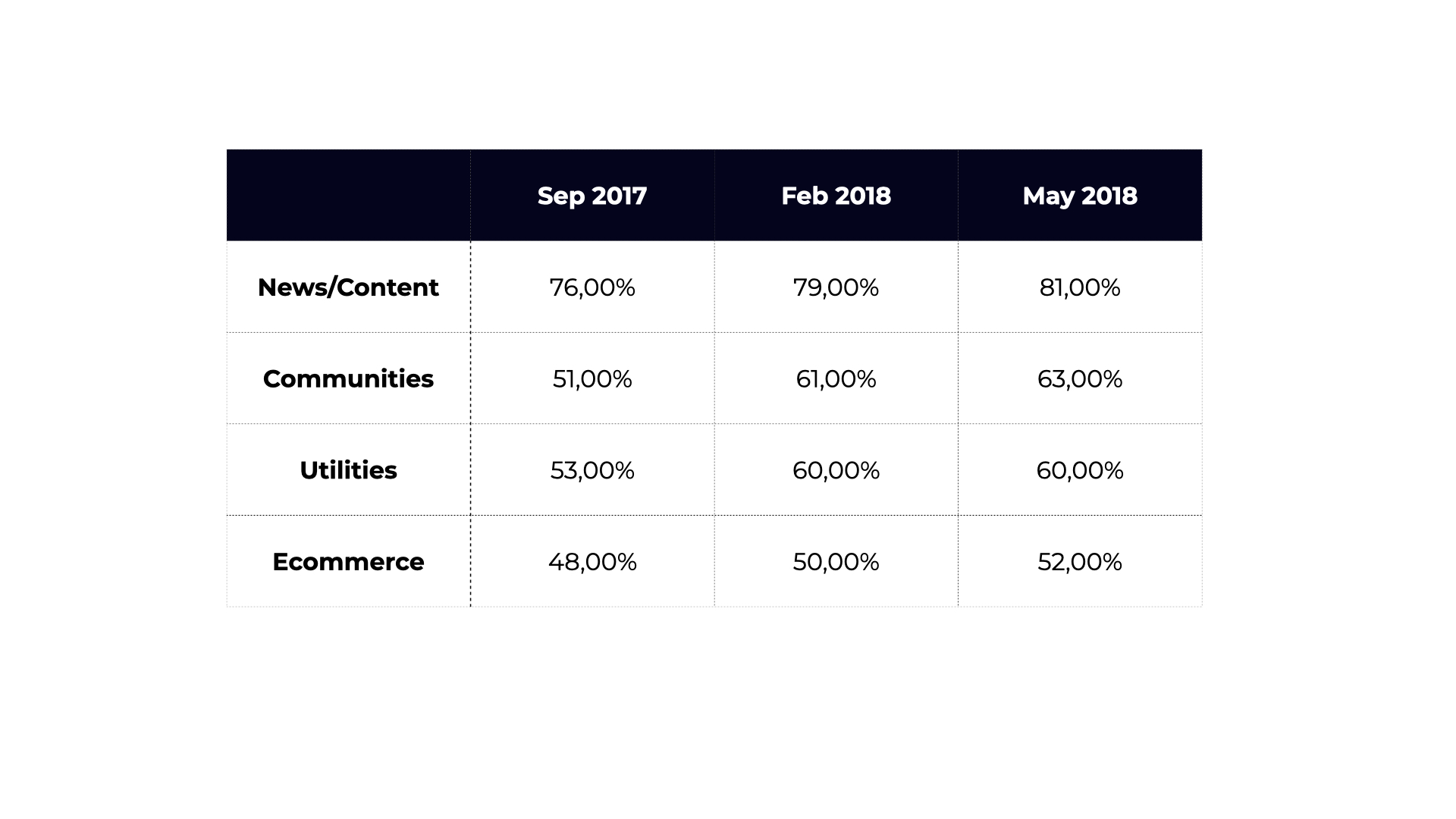

Nevertheless, only 21% of marketers have a good understanding of header bidding.

Header Bidding, what is it?

Header Bidding RTB advertising is an advanced technology that allows publishers to offer their ad inventory to multiple ad exchanges at the same time, instead of presenting the inventory in turns. Various advertisers bid simultaneously and in real-time, having the same bidding opportunities. Header Bidding benefits both advertisers and publishers. Advertisers get the right to access and pay for premium quality inventory before it is sold in the first rounds of the waterfall auction model, while publishers can increase their profits and maximize their revenues. Pre-bidding allows every publisher to sell every ad impression to the right bidder, at its true market value.

From Waterfall to Header Bidding

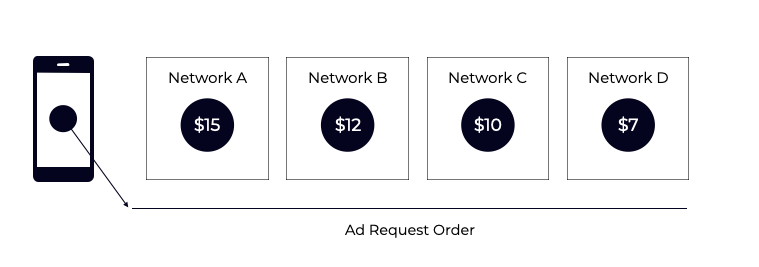

For years, the traditional waterfall has been the preeminent model in programmatic advertising. Waterfalling, also known as “daisy-chaining”, is defined as a type of ad bidding where the ad request cascades down from one ad network to the next ones until one of them is able to fill the request. In a traditional waterfall model, ad networks are ranked based on their historical eCPM performance.

Typically, publishers and advertisers have conflicting interests: for every ad impression, advertisers want to pay less and publishers to want to earn more. The waterfall approach was not intended to please either party and it reveals four main problems.

Problems of the waterfall approach

1. Often, traditional waterfall relies on inaccurate historical eCPM performances.

Suppose Network A has a historical eCPM performance higher than Network B. In a traditional waterfall model, Network A would be ranked first. Now suppose that Network B has a new ad campaign worth $20 eCPM. Due to its historical eCPM performance, Network B would still be positioned behind Network A, limiting its opportunity to serve its high-value ad and reducing publishers’ revenues. In a waterfall model, publishers ad revenue outcomes will always be suboptimal rather than optimal.

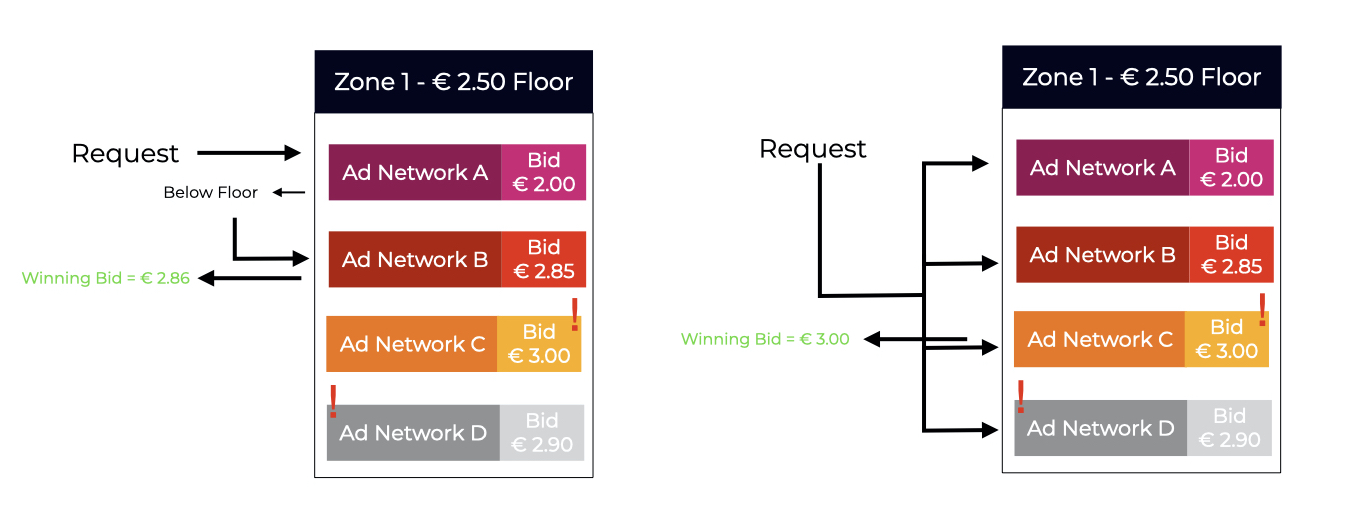

Price floors allow overcoming this problem. A price floor is defined as the minimum bid an ad placement is willing to consider for an ad to be served. Introducing price floors is also essential to solve the second problem relating to the waterfall approach.

2. Traditional waterfall holds higher value ads back

Price floors allow ad networks to place ad bids based on the true value of the ad itself rather than on their historical eCPM performance. Highest earning ads will be served first, regardless of their waterfall positioning. Price floors benefit both advertisers and publishers. Advertisers have more transparency in deciding if placing or not a bid, while publishers have more power in assigning value to ad units, protecting the minimum value of their impressions.

Price floors come in handy in various ways, but publishers still don’t have optimal revenues outcomes.

3.Waterfall adopts a second-price auction model, reducing publishers’ earnings

Second-price auction model diminishes publishers’ earning while satisfying the interests of advertisers in paying a lower price for every ad impression. As a matter of fact, the second-highest bidder determines the sale price of an impression.

Suppose advertiser A places a bid of $7 eCPM, advertiser B places a bid of $4 eCPM and advertiser C places a bid of $3 eCPM. In a fair situation, the publisher should earn $7 eCPM. Invece In a second price auction model, the publisher will earn just a penny over $4 eCPM rather than $7 eCPM. The advertiser placing the winning bid will pay $5 eCPM as well.

Price floors mitigate the effects of the second-price auction for publishers, helping them earn much closer to the winning top bid. Take into account the scenario above with a price floor of $6 eCPM. The winning bid would still be $7 eCPM but the publisher will earn a cent over the price floor, meaning $6.01 rather than $4.01 eCPM.

4. Ad latency is an emblem of Waterfall model

Ad latency has always been one of the main issues of the waterfall model. Since the ad request cascades down from one ad network to the next ones until one of them is able to fill the request, the more the requests the longer the latency.

Parallel bidding, as Header Bidding is also known, reduces ad latency by up to 65% by sending out ad requests simultaneously.

Our header bidding solution: how to help publishers earn more

We provide publishers with an easy and independent platform developed to maximize revenues through an advanced header bidding solution. Our Instal for Monetization solution allows collecting data from the auction of every impression to predict and set optimal floor price rules across several ad exchanges.